EDLDR551:

Lesson 2: Concepts of Curriculum

Lesson 2: Concepts of Curriculum

Lesson Overview

This lesson introduces fundamental concepts in curriculum study: different definitions of curriculum, types of curriculum, Schwab’s idea of four commonplaces in education, and steps of curriculum analysis outlined by Posner (2003).

Lesson Objectives

Upon successful completion of this lesson, you will be able to

- describe three common definitions of curriculum

- describe different types of curriculum

- articulate their own theoretical and practical definition of curriculum that will assist their thinking about educational issues

- describe Schwab’s four commonplaces that shape curricular design and practice

- discuss the major steps involved in curriculum analysis; and

- identify a specific school curriculum program and begin the process of analyzing its content.

Lesson Readings & Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 2 Course Schedule.

Basic Concepts of curriculum

These are the basic considerations in curriculum work.

- What is curriculum?

- What are curriculum types?

- What are curriculum perspectives?

- What are curriculum commonplaces?

- What are the steps in curricular analysis?

What is curriculum?

Posner (2003) identifies these fundamentals of curriculum:

- Scope and sequence: The depiction of curriculum as a matrix of objective assigned to successive grade levels (i.e., sequence) and grouped according to a common theme (i.e., scope).

- Syllabus: A plan for an entire course, typically including rationale, topics, resources, and evaluation.

- Content outline: A list of topics covered organized in outline form.

- Textbooks: Instructional materials used as the guide for classroom instruction.

- Course of study: A series of courses that students must complete.

- Planned experiences: All experiences students have that are planned by the school, whether academic, athletic, emotional, or social.

Three Definitions of Curriculum

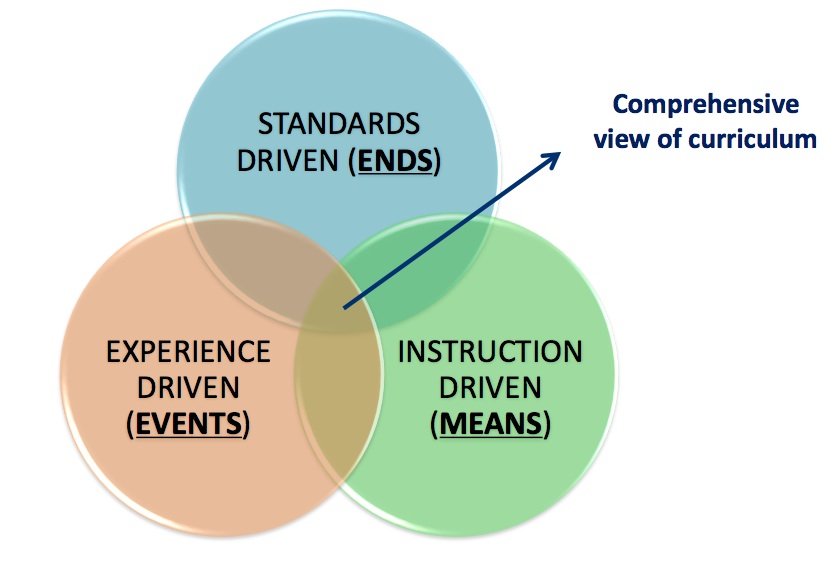

Posner (2003) goes on to identify three common definitions of curriculum:

- Curriculum is the content or objectives for which schools hold students accountable. Curriculum represents the expected ends of education.

- Curriculum is a set of instructional strategies teachers plan to use. Curriculum represents the expected means of education.

- Curriculum is students’ actual experiences or learning. Curriculum is a report of actual educational events, not about means or ends.

Comprehensive View of Curriculum

Types of Curriculum

Posner (2003) distinguishes types of curriculum:

- Official curriculum: The curriculum described in formal documents.

- Operational curriculum: The curriculum embodied in actual teaching practices and tests.

- Hidden curriculum: Institutional norms and values not openly acknowledged by teachers or school officials.

- Null curriculum: The subject matters not taught.

- Extra curriculum: The planned experiences outside the formal curriculum.

Schwab's Four Commonplaces

According to Schwab (1973), the following four bodies of experience must be represented in any group engaged in curriculum work.

- Subject matter: There must be someone who is familiar with the nature of the subject matter in the instructional materials under consideration. For example, in a group undertaking the task of revising science education curriculum, there must be a member in the group who knows the science content in the instructional materials as well as what it means to be engaged in scientific inquiry.

- Learners: There must be someone who is familiar with the children (students) as beneficiaries of the curriculum under consideration. For example, there must be a member in the group who understands how children learn, their developmental and motivational needs, etc.

- Milieu: There must be someone who is familiar with the various milieu (classroom, school, family, community) in which learning will take place. For example, there must a member in the group who understands the family culture, parental attitudes, and parenting styles of the community in which curriculum may be implemented.

- Teachers: There must be some who is familiar with the characteristics of teachers, their knowledge of the subject matter and instructional pedagogy and the attributes of teachers as adopters of curricular innovation. For example, there must be a member in the group who understands what teachers are likely to know and how flexible they are and likely to learn new curricular approaches and methods of teaching.

According to Schwab (1973), it is vital for curriculum workers is to remember that each of the four bodies of experience is important to the curriculum making enterprise as a whole. "Coordination, not super-ordination-subordination, is the proper relation of these four commonplace" (p. 509).

Curricular Analysis: Key Steps

The process of Curriculum Analysis outlined in Posner, 2003.

Before we can get to Step Four: Curricular Critique, we need to understand the first three steps of Curriculum “Background,” “Proper” and “Implementation.” In the first step, we examine "what is behind the curriculum?” Here, we try to understand the perspective(s), the situation and the problem that have resulted in the development of the program. In the second step, we examine "what is in the curriculum”? Here, we try to understand how the program has been put together and what are media and content structures used by the program developers. In the third step, we examine "what has happened or can potentially happen when the program is implemented?" Step Four, the curriculum critique, summarizes your analysis of all three steps.

A sound curricular analysis is determined by three criteria:

- Does the author critically examine “what is behind the curriculum” (purpose, goal, perspectives, assumptions)?

- Does the author critically examine “what is in the curriculum” (the nature of the content, basis for its selection, vertical and horizontal organization of subject matter)?

- Does the author critically examine “what are the experiences with the curriculum” (how curriculum may be taught, what methods may be used, how the program success may be judged, the frame factors)?

Lesson 2 Activities

Step 1: Curriculum Analysis Paper (Curriculum Background)

Choose a program for curriculum analysis paper: Each participant will conduct an analysis of content-specific, K–12 curriculum program (e.g., CHEMCOM chemistry program, Everyday Math program, Full Option Scope and Sequence Science (FOSS) program, TROPHIES, GLOBE program, etc.). Refer to the guidelines on “how to choose a curriculum for analysis” in Textbook 1 (pp. 29–30) and then choose a program for your curriculum analysis paper. State the name of the program on the Globe: Sample Curriculum Program Discussion along with your rationale for the choice.

There are four steps involved in your analysis of curriculum program (Please refer to Lesson 2 and Steps of Curriculum Analysis Chart).

- Step 1

- Curriculum Background is described in Lesson 2, activity 1.

- Step 2

- Curriculum Proper is described in Lesson 7, activity 1 and Lesson 8, activity 1.

- Step 3

- Curriculum in Use is described in Lesson 9, activity 3 and Lesson 10 activity 4.

- Step 4

- Curriculum Critique is described in Lesson 11, activity 5 and Lesson 12, activity 2.

Write Step 1 of Curriculum Analysis:

- Read the first three chapters in Textbook 1 (pp. 1–65).

- Refer to the checklist on curriculum analysis paper.

- Make sure you understand each of the following prompts under Step 1: Curriculum Background

- Documents available: Describe all the documents and resources you will use in your analysis, including teacher guide, student textbook, program website, marketing pamphlets, brochures, program evaluation report, etc. Include all the limitations you find in materials and documentation provided by the program designers.

- People involved in development of the program: Describe all the people involved (content experts, psychologists, teachers, students, parents, etc.) in the development of the program and their roles. Schwab has suggested that at least one representative from each of the four commonplaces—subject matter, teacher, learner and the milieu—should be included in the curriculum deliberations. Is that true for your program? Are there any blind spots?

- Situation that led to development of the program: Are there any situational factors that prompted the curriculum designers to develop this program? What is the underlying problem addressed by the program? For example, developers of a literacy program may perceive the "real problem" underlying low levels of media literacy is that most students are unable to judge the credibility and accuracy of information presented in different media formats.

- Perspective on curriculum, teaching and learning outlined in the program: Developers of two different programs may apply different approaches or perspectives in response to the same problem. Posner (2003) outlines five perspectives: "traditional perspective" (focus on "basic" skills, facts, and terminology), "experiential perspective" (focus on child's interest, problem, and life-experiences), "structure of discipline perspective" (focus on discipline or subject matter), "behavioral perspective" (focus on specific and measureable outcomes), and "cognitive perspective (focus on construction of personal understanding and meaning-making). Which of the five perspective(s) are dominant in your program? Perspective(s) are normally stated in the introduction part of the program materials (e. g., in the teacher guide). Perspective(s) may be implicit or explicit.

- Epistemological assumptions of the program: What are the implicit or explicit assumptions about the nature of knowledge? For example, epistemological assumptions about the nature of literacy could be that "literacy is an individual's ability to read, write, speak in English, compute and solve problems at levels of proficiency necessary to function on the job, in the family of the individual and in society" (National Institute of Literacy, 1998) or "literacy is the technical mastery of particular skills necessary to decode simple texts (e.g., street signs and instructions), familiarity with particular linguistic traditions or bodies of information, and the ability to decode the ideologies embedded in texts and media such as television and film in order to reveal their selective interests and perspectives" (McLaren, 1988).

- Psychological assumptions of the program: What are the implicit or explicit assumptions about "how children learn"? For example, developers of a literacy program may assume that children must be allowed to follow their own interests to personally discover the literacy content that they find interesting and relevant to their own lives and children learn best when learning is an enjoyable, happy experience.

- Pedagogical assumptions of the program: What are the implicit or explicit assumptions about "what is the best way to teach"? For example, the developers of a literacy program may assume that teachers must assist children with the "construction" of knowledge and reject teacher-directed knowledge transmission.

- Write a 1–2 page (single-spaced) curriculum background of the program you have chosen. Remember, this is a description of what led to the program development and the actual deliberations of the curriculum project team. Your analysis should address each of the seven prompts listed above.

Rubric for Curriculum Analysis Paper

| Criteria | Full Marks | Partial Marks | No Marks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Curriculum background: Assumptions and perspectives | 10.0 pts

Clearly and thoroughly clarifies the ideological, epistemological, psychological and pedagogical assumption behind a particular program | 5.0 pts

Partially clarifies the ideological, epistemological, psychological, and pedagogical assumption behind a particular program | 0.0 pts

Does not clarify the ideological, epistemological, psychological and pedagogical assumptions behind a particular program |

| Step 2: Curriculum proper: coherence and alignment | 10.0 pts

Clearly and thoroughly examines the nature of content, basis for its selection, vertical and horizontal organization of subject matter, and coherence between intended and designed curriculum | 5.0 pts

Partially examines the nature of content, basis for its selection, vertical and horizontal organization of subject matter, and coherence between intended and designed curriculum | 0.0 pts

Does not examine the nature of content, basis for its selection, vertical and horizontal organization of subject matter, and coherence between intended and designed curriculum |

| Step 3: Curricular implementation | 5.0 pts

Clearly and thoroughly describes the "frame- factors" that can shape the implementation of a particular curricular program | 2.5 pts

Partially describes the "frame- factors" that can shape the implementation of a particular curricular program | 0.0 pts

Does not describe the "frame-factors" that can shape the implementation of a particular curricular program |

| Step 4: Curriculum critique | 5.0 pts

Articulates clearly and thoroughly the strengths and weaknesses of the curriculum program, and how it can be adapted to maximize its benefits and minimize its limitations | 2.5 pts

Partially clarifies the strengths and weaknesses of the curriculum program, and how it can be adapted to maximize its benefits and minimize its limitations | 0.0 pts

Does not articulate clearly the strengths and weaknesses of the curriculum program, and how it can be adapted to maximize its benefits and minimize its limitations |

Lesson 2 Discussion of Readings from Textbook

Every participant will frame 1–2 discussion questions on readings for the week and submit his or her questions on the online discussion forum. The instructor will assign a discussion leader to the Reading Discussion Leaders page. As the discussion progresses, the role of discussion leader is to periodically restate the main points from the discussion. The idea is to keep a clear focus and keep the discussion on track in the same way that a discussion leader would do in a brick and mortar classroom. All participants are expected to respond to a minimum of 2 posts written by classmates during the week. Neither participants nor discussion leaders are required to respond to all of the postings. Please note that posts such as “I agree” or “I disagree” are not sufficient.

Note that this discussion is set for “post first,&rdquo which means you will not see the postings of your classmates until you post your own. Therefore, the first thing you should do is to post your discussion questions on the readings for the week.

Readings for this week: Textbook 2

- Chapter 1: Conceptualizing curriculum (pp.1–22)

Globe: Sample Curriculum Program Discussion

Go to the GLOBE website and familiarize yourself with the GLOBE program. Download the online documentation “The GLOBE Program Overview (pp. XII–XIV)” under “Teaching & Learning,” then click GLOBE Teachers’ Guide, then click your language preference under the Teacher's Guide Introduction. In the online discussion forum, exchange views on the situation or problem that resulted in the development of GLOBE program, the perspective GLOBE program represents, and the epistemological, psychological and pedagogical assumptions in the GLOBE program.

Sample Curriculum Program

School programs are based on certain curricular assumptions which include assumptions about epistemology (what counts as knowledge?), psychology (how children learn?), pedagogy (what is the best way to teach?), ideology (what knowledge is most worth and who controls it?), and morality (What moral ideas ground our stance toward teachers and students?). The depth and richness of your curricular inquiry will benefit from analysis of curricular assumptions. The objective of this activity is to analyze epistemological, psychological and pedagogical assumptions in your chosen curriculum program.

Epistemological, psychological and pedagogical assumptions in GLOBE program: In GLOBE Teacher’s Guide (introduction section, page XIII), the authors note:

As a science education program, GLOBE neither begins nor ends with data collection. Scientists collect data to gain understanding, and students can do the same. Teachers are encouraged to stimulate and reinforce their students’ natural interest in their surroundings...GLOBE provides materials and infrastructure to support students in carrying out the process of science, which often called inquiry

On page XIII, first line, authors also note that “GLOBE is science and education, not just science education.” What does it mean to say that “GLOBE is science and education, not just science education”? Often, curriculum designers assume that science is done by scientists and the role of science teachers is to teach the layman (or child) what has already been discovered by scientists. This is generally called “science education”. A major epistemological assumption behind GLOBE is that everyone can do science, not just scientists. According to the designers of GLOBE, children can do “real science” because in GLOBE teachers and students join with research scientists to form broadly distributed research teams and students collect data that is valuable to each research team’s work on a particular scientific inquiry (p. XIII). The designers of GLOBE assume that science is a human activity that can be done by anyone. In GLOBE Teacher’s Guide, the idea of “child as scientist” is an important epistemological assumption. Consistent with this assumption, it is assumed that children learn science best when they are engaged in authentic, collaborative, inquiry-based activities (psychological assumption). The teacher’s role is to stimulate the child’s curiosity and to provide the instructional support to carry out the process of science (pedagogical assumption), which is often called inquiry.