HLS875:

Lesson 1: Origins and Context of U.S. Homeland Security Law

Origins and Context of U.S. Homeland Security Law

Law is an inseparable element of Homeland Security; it is fundamental to the creation of the U.S. as a nation of laws and justice, and to it's citizens' understanding of the role and purpose of government. The Constitution, as the supreme law of the land, contains provisions that enable the noble principles of unalienable rights while avoiding the tyranny enunciated in the Declaration of Independence, a guiding historical covenant that laid the foundation for the Constitution as a permanent binding contract. Both are very relevant today in defining and achieving homeland security. In particular, the Constitution provides an authoritative framework for the many derivative laws, directives and decisions that are the result of actions of the three branches to fulfill its purpose.

The nation's approach to homeland security is based on the inseparability of law from unalienable rights and the pursuit of individual self-determination. The powers that belonged to the people at the time the Constitution was ratified, were retained by the people--except for those powers granted to the federal government, or to the States. Homeland Security law is thus grounded in the Constitution and the many actions taken, consistent with its provisions: laws enacted by Congress and the legislatures of the states; executive orders and directives issues by the President and Governors; and court decisions determining whether the laws and directives are Constitutional, and thus legal.

Query:

By designing a form of governance that was limited and inefficient, yet potentially very powerful, were the Framers not ensuring that the citizens would have neither freedom nor security?

Origins and Context of U.S. Homeland Security Law

Lesson Overview:

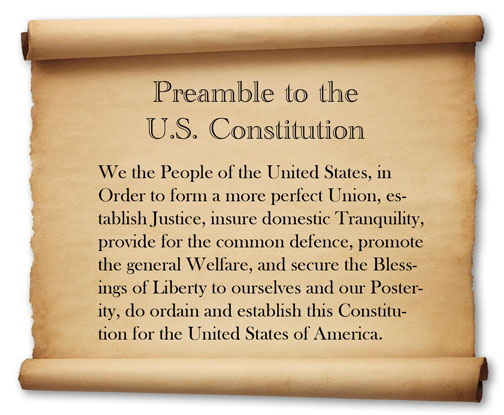

This lesson examines the foundation and underlying principles of homeland security law, as enunciated in key provisions of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Federalist Papers. Those historic documents contain precepts for the central organizing principles of self-evident truths, unalienable rights, and terms of governance, such as limited government with the consent of the governed, and the right to remove an oppressive government. So deeply ingrained are those principles that the discussion begins with the experience of the early settlers of the U.S. in their struggle for survival, prosperity and the preservation of their values. The lesson offers a context for the requirement of individual rights and freedom, the responsibilities associated with the assumption of risk, and the role of government in the enterprise of providing a structure in which the missions articulated in the Preamble can be realized.

Objectives:

- Describe the attitude of the U.S. citizen toward freedom and responsibility, and the role of government

- Explain the underlying principles upon which the democratic republic of the U.S. was founded

Please complete the assignments and readings outlined on the course schedule for this week.

Lesson Road Map

Readings:

- Lesson 1 online commentary

- Declaration of Independence (Available on the Homeland Security Research Guide - see Note below)

- U.S. Constitution: Preamble; Articles I, II, and III; and the first 10 Amendments (Research Guide)

- Federalist Papers Number 1, 10, 42, 51 (Research Guide)

- Bush v. Gore - 531 U.S. 98 (2000)

(https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/531/98/) - Gulf, C. & S. F. R. CO. v. Ellis, 165 U.S. 150, 159-160 (1897)

(https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/165/150/)

Note: Many course readings can be found by using the Penn State University Libraries Homeland Security Research Guide - http://guides.libraries.psu.edu/hls

Homeland Security Law

Homeland Security Law consists of a complex body of Constitutional provisions, legislative enactments, executive regulations and directives, and judicial decisions designed to ensure protection from man-made attacks or natural disasters since 1789. The constant trade-off between ensuring security while preserving individual freedoms has been a key factor in the relationship between the citizens and the governmental controlling authorities since 1789, or 1776, or even 1607, depending on how vital interests such as survival, prosperity, and values are perceived. It certainly was very much on the minds of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, as well as the framers and ratifiers of the Constitution, and it has concerned decision makers at the federal and state level ever since. The deep-seated sense of entrepreneurial freedom, coupled with those unalienable rights expressed in the Declaration and made the supreme law of the land in the Constitution, has become an integral attribute of the U.S. view toward security and the role of government in providing it. The lack of imagination in applying the firewalled instruments of statecraft relevant to the terrorist attacks of 2001, or the inept coordination of the local, state, and federal response to the natural disaster of Katrina in 2005 certainly resulted in considerable laws, directives and court decisions concerning homeland security, but a cursory look at the broad treatment of that existential concept of security could go back as far as 1607, and the first settlement and creation of infrastructure on land that was to become the U.S.

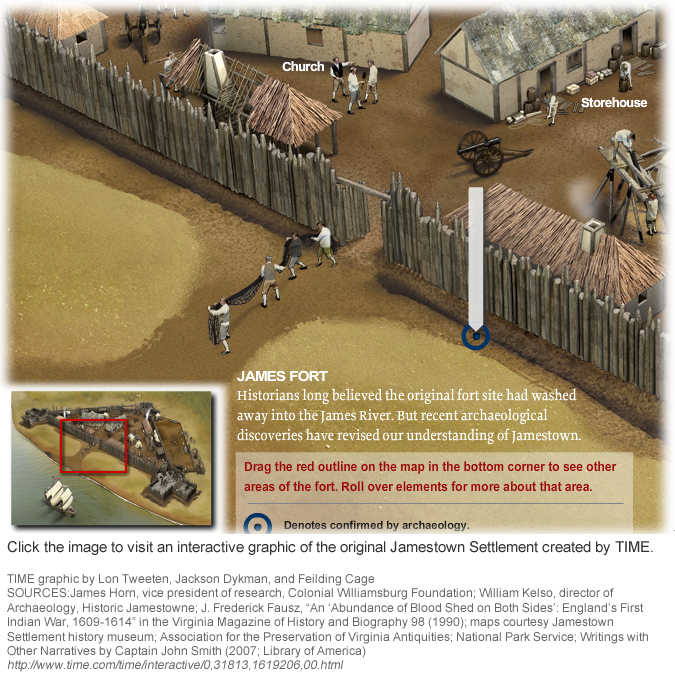

Although the breadth and subject area of homeland security law is very diverse, with the area of focus often shifting quickly, due to current events of both human and natural causes, it is obvious that the threats and challenges have been part of the nation’s environment since long before it’s founding. Thus, Homeland Security law arguably dates back to the Jamestown settlement in 1607, when the Virginia Company explorers first sought safety for themselves and their property, while establishing a foothold in an adverse environment already in the rightful possession of those inhabitants, who preceded them. The venture settlers quickly constructed a wooden fort to protect their initial infrastructure, which would consist of a church for their values, a store for their prosperity, and homes for their families, and to survive, out of the range of guns from Spanish ships on the Chesapeake Bay, and from imminent internal attacks from the local Algonquians. Those threats, plus starvation, bad weather, and various pandemics resulted in the issuance of stringent directives by the putative head of government, Captain John Smith, who inspired the settlers to assume the risks associated with an existence, ripe with conflict. Although they nearly succumbed to physical and spiritual failure, especially during Smith’s absence over the starving winter a few years later, they ultimately displayed great resilience and found the beneficial use of other means of perseverance, such as diplomacy, to enable co-existence with their erstwhile adversaries. They also created a representative assembly to meet, appropriately, in their church, with the greater goal of expanding that form of governance uniformly to the entire region of Virginia.

Homeland Security and the Early Settlers

As mentioned previously, Homeland Security can trace its history to the days when the earliest settlers made the English colonies of North America their home. Those pioneers faced a multitude of threats, including famine and disease, by Indians, and other European powers. Far from England, and in the absence of an organized security force, their vulnerability induced them to organize into militias. The first American militia, the true forerunner to the National Guard, was formed in the Colony of Virginia in 1607. The First Representative Assembly in the New World convened on July 30, 1619, and the General Laws and Liberties of the Massachusetts Bay Colony," were published in 1648. The infrastructure was in place for sovereignty and self-defense although it would take another century for that to be contemplated as such.

The colonies operated as dependencies of the Crown, and colonial officials held their offices at the pleasure of the Crown. The actual day-to-day administration of colonial affairs was the King’s Privy Council, a group of advisors appointed by and accountable to the King. Many unreasonable demands were made and incidents of tyranny were prevalent. By 1776, the oppression of an occupying power became intolerable, and the Colonialists began a 15 year odyssey from dominated colony to the sovereign United States of America.

If the following content does not appear, click the following link to be directed to the external site - https://www.history.com/topics/jamestown/videos

(Duration 00:02:45)

The short History Channel video above provides a brief description of what the Jamestown settlers faced. The Jamestown settlers continued to experience the usual threats to survival, prosperity and values, as did other settlements that similarly persevered over the next century to eventually become part of the thirteen original colonies. Independently, they sought sufficient security to allow for the pursuit of religion and prosperity, while collectively they experienced the tyranny of their colonial ruler, King George III. That abuse was as direct a threat to homeland security as oppressed citizens could be subjected to, with occupation forces on their land and in their homes, and little recourse available in court or elsewhere. To resolve matters of internal conflict, they would look to an equitable settlement from within or the vestiges of common law (judge made precedent) they had brought over from England. Overall, those initial years were marked by the assumption of great risk that nearly ended in the demise of the settlers.

The Context of Homeland Security Law

The British government provided protection, albeit under tyrannical conditions, to the colonialists, and the local government frequently had to resort to its own defenses. By the 1760's, as the demands from the Crown increased and became more unreasonable, it was intolerable to those who had envisioned a freer life; resistance was manifested in many ways, from refusal to pay taxes, to the Boston tea party, to actual skirmishes with British troops. These acts went directly against the sense of freedom and self-determination which the settlers considered to be the reason for their move to the new world.

The Covenant

The sum of the Colonialists' attitude toward an unfair distant ruler, and their reaction to the loss of freedom was articulated in the Declaration of Independence, a watershed communiqué in the history of the human political experience. That remarkable document made the case for asserting the improvement of one’s lot, and provided a formula for better governance. It recognized the validity of the global community, and the responsibility of nations to respect the dignity and welfare of their citizens. And, it legitimatized the right to overthrow an abusive government and assert national self-determination. It laid out a vision for a functional, limited government, with the consent of the governed; and, it provided a bill of particulars, listing those unacceptable abuses. All that remained was a political structure in which those ideals of a just society could be realized.

The Contract

After the Declaration, and the protracted war with Great Britain, during which the Continental Army coped with an ineffective Confederate Congress of the 13 free colonies, the need for a more united and effective government became obvious. Many vulnerabilities continued, with internal instability, based on a loose rule of law, and ineffective government under the Articles of Confederation (weak executive, powerless legislature and no discernible judiciary), and external threats from European powers and Indian tribes. The culminating event occurred in 1787 with the Convention in Philadelphia ostensibly to address the current government, but which resulted in the drafting of the Constitution. The remarkable undertaking by visionary framers would incorporate the noble concepts as well as the threats enunciated in the Declaration of Independence, and provide a framework for a federal government with stated purposes:

The structure for a national or federal government with three separate branches sharing powers and thus checking and balancing each other, all with limited powers, the rest of which were reserved to the States and the people was a formula for a successful nation, and a structure in which it could evolve. Over two centuries later a dynamic form of governance endures! See the Federalist Papers for additional explanations of the intent of the Framers.

The Treatment of Homeland Security in the Basic Documents

In 1776, when the advocates of independence asserted the claim to unalienable rights, based on a version of divine or natural law, they implied a right to basic security for the homeland and its inhabitants. The statement of principles together with the description of challenges to them is not unlike the narrative used in current security strategies.

Since 1607, when the first entrepreneurs and artisans moved from ship to uncertain shore, one of the motivating factors was that of being free. Two hundred and ninety years later, the Supreme Court articulated that sentiment in the case of Gulf, C. & S. U. R. CO. v. Ellis, 165 U.S. 150 (1897), calling the Declaration of Independence the first official action of this nation, and implying it was the foundation of government:

"While such declaration of principles may not have the force of organic law, or be made the basis of judicial decision as to the limits of right and duty, and while in all cases reference must be had to the organic law of the nation for such limits, yet the latter is but the body and the letter of which the former is the thought and the spirit, and it is always safe to read the letter of the Constitution in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence. No duty rests more imperatively upon the courts than the enforcement of those Constitutional provisions intended to secure that equality of rights which is the foundation of free government. “

Eleven years later, mindful of the noble principles and the list of threats contained in the Declaration of Independence, the framers addressed the internal instability and external threats of the previous decade by designing a structure to form, establish, ensure, provide, promote and secure in whatever manner it would take to create a viable nation. Three of the framers then anonymously advocated ratification by way of persuasive arguments, now known as the Federalist Papers, appearing as op-eds in New York paper.

The Constitutional structure provided brilliantly for the freedom to enjoy life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and enrichment through self-determination, to include not being put in harm’s way---and all that with only sporadic government protection and intervention! Of course, the cascade of statutes and executive actions, in response to the wars, conflicts, and disasters that ensued, has created a legal thicket surrounding security issues--but that is the price for a government with such a far ranging mission!

The Connection Between the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence

The signing of the Declaration of Independence is the recognized date for U.S. sovereignty and independence, a document in which the Founders articulated the core values on which the mission of the Constitution was to be based. The Constitution was then dated in terms of the signing of the Declaration, thereby manifesting its relationship as the second great document in an historical sequence of works already in progress.

The Supreme Court has reflected on the relationship between the Declaration and the Constitution on a number of times as being one that is inseparable and interdependent. The Court declared in Gulf, C. & S. F. R. CO. v. Ellis, 165 U.S. 150, 160 (1897) that the Constitution is the body and letter of which the Declaration of Independence is the thought and the spirit, and it is always safe to read the letter of the Constitution in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence.

Another reference to the Declaration was made in Cotting v. Godard, 183 U.S. 79, 94 (1901):

The first official action of this nation declared the foundation of government in these words: 'We hold these truths to be selfevident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.' While such declaration of principles may not have the force of organic law, or be made the basis of judicial decision as to the limits of right and duty, and while in all cases reference must be had to the organic law of the nation for such limits, yet the latter is but the body and the letter of which the former is the thought and the spirit, and it is always safe to read the letter of the Constitution in the spirit of the Declaration of Independence. No duty rests more imperatively upon the courts than the enforcement of those constitutional provisions intended to secure that equality of rights which is the foundation of free government.

The Declaration, and the Constitution, remain fully relevant today in the fabric of the nation’s principles, and in the pursuit of its purpose.

The Difference between National Security and Homeland Security

Security of citizens, their values, and their homeland has traditionally been a paramount reason for a controlling authority or government agency in some form within the U.S. The functioning of that entity has included legal processes tied to the mission of providing security. Depending on the perspective and jurisdiction, the authority could have an external national security function, or it could be focused internally on homeland security.

Between 1607 and 1776, early colonialists relied in part on Great Britain, which provided security with a two edged sword, but for the most part, they assumed the risk of threats in return for freedom. Vital interests of survival, prosperity and values can be traced to Jamestown, and the rudimentary civil organization put in place there to provide such security. After the Constitution was ratified and the U.S. federal government assumed the role of providing for the common defense, the national security establishment slowly emerged, after 1789, in response to evolving threats and retained primarily an external focus. Force, diplomacy, and intelligence were directed globally.

The National Security Act of 1947, and follow-on statutes and policies, ensured that the separation would remain between the domestic and the external use of instruments of statecraft, whether Intelligence or military force. That separation satisfied the concerns of those who wished to keep traditional national security activities removed from domestic involvement where such action could infringe on freedoms. The national security apparatus evolved into a top-down, centralized, secretive, externally oriented enterprise. Responses to domestic matters, especially natural disasters, were left, for the most part, to state and local authorities with minimal assistance from federal entities.

After 9/11, with the rapid development of homeland security organizations and legal authorities, much of the focus changed, with increased pressure to share information among Intelligence and law enforcement agencies, and to use executive branch capabilities in support of civil authorities. And, most notably, the Department of Homeland Security has a major counter-terrorism role in both a domestic and international context. In contrast to the national security establishment, the emerging homeland security enterprise can be characterized as local, bottom-up, decentralized, and transparent in nature.

Obviously the distinction between national and homeland security continues to blur, and from a legal point of view, laws are laws. In 2001, the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century, the Hart–Rudman Commission, proposed creating a National Homeland Security Agency that would address all security concerns. In the post Cold War environment of 9/11 and Katrina, there has been a lessening in the distinction of the roles and missions of national and homeland security. In Presidential Study Directive – 1, President Obama proclaimed that, “Homeland Security is indistinguishable from National Security – conceptually and functionally, they should be thought of together rather than separately.”

Summary

From the safety of the first settlers to the current well being of millions of citizens, the concerns for survival, prosperity, and preservation of values have been the same: how do citizens find a state of security and freedom in which to pursue life, liberty and happiness?

The Difference between National Security and Homeland Security

Security of citizens, their values, and their homeland has traditionally been a paramount reason for a controlling authority or government agency in some form within the U.S. The functioning of that entity has included legal processes tied to the mission of providing security. Depending on the perspective and jurisdiction, the authority could have an external national security function, or it could be focused internally on homeland security.

The Early Days

Between 1607 and 1776, early colonialists relied in part on Great Britain, which provided security with a two-edged sword, but for the most part, they assumed the risk of threats in return for freedom. Vital interests of survival, prosperity and values can be traced to Jamestown, and the rudimentary civil organization put in place there to provide such security. After the Constitution was ratified and the U.S. federal government assumed the role of providing for the common defense, the national security establishment slowly emerged, after 1789, in response to evolving threats and retained primarily an external focus. Force, diplomacy, and intelligence were directed globally.

National Security Act of 1947

The National Security Act of 1947, and follow-on statutes and policies, ensured that the separation would remain between the domestic and the external use of instruments of statecraft, whether Intelligence or military force. That separation satisfied the concerns of those who wished to keep traditional national security activities removed from domestic involvement where such action could infringe on freedoms. The national security apparatus evolved into a top-down, centralized, secretive, externally oriented enterprise. Responses to domestic matters, especially natural disasters, were left, for the most part, to state and local authorities with minimal assistance from federal entities.

9/11

After 9/11, with the rapid development of homeland security organizations and legal authorities, much of the focus changed, with increased pressure to share information among Intelligence and law enforcement agencies, and to use executive branch capabilities in support of civil authorities. And, most notably, the Department of Homeland Security has a major counter-terrorism role in both a domestic and international context. In contrast to the national security establishment, the emerging homeland security enterprise can be characterized as local, bottom-up, decentralized, and transparent in nature.

U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century and Presidential Study Directive 1

Obviously the distinction between national and homeland security continues to blur, and from a legal point of view, laws are laws. In 2001, the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century, the Hart–Rudman Commission, proposed creating a National Homeland Security Agency that would address all security concerns. In the post Cold War environment of 9/11 and Katrina, there has been a lessening in the distinction of the roles and missions of national and homeland security. In Presidential Study Directive – 1, President Obama proclaimed that, “Homeland Security is indistinguishable from National Security – conceptually and functionally, they should be thought of together rather than separately.”

National Security Strategy (2015)

This trend has been reinforced by the National Security Strategy of 2015 (https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/2015_national_security_strategy.pdf) that among other things combines a call to strengthen national defense with a call to reinforce homeland security.

The Strategy also argues that homeland security is a prerequisite for national security. Pointing out that "the United States government has no greater responsibility than protecting the American people" (p. 7), the National Security emphasized the importance of "reinforcing homeland security" in a overall effort to make to nation capable to act at home and abroad to deliver security to the citizens in a comprehensive approach – with a notable focus on law enforcement aspects:

Summary

From the safety of the first settlers to the current well being of millions of citizens, the concerns for survival, prosperity, and preservation of values have been the same: how do citizens find a state of security and freedom in which to pursue life, liberty and happiness?

Assignments:

Lesson 01 Discussion Forum

- List the most significant truths and freedoms enunciated in the Declaration of Independence. Similarly, list the most significant threats to those freedoms that are described therein. Where do you see the parallels to the homeland security mission space of today?

- Post your response to the Lesson 01 Discussion Forum and reply to at least two other student postings.

Bush v. Gore - Lesson 01 Dropbox

- Read Bush v. Gore, and in one to two pages describe the homeland security issue to which it pertains. List the parties that are involved and the controlling authorities that are discussed in the opinion.

- Post your 1-2 page paper to the Lesson 01 Dropbox.