LHR305:

Lesson 9: Pay Structures

Lesson Overview

To this point in the course we have focused on the important functions related to human resource management that recruit, select, train and manage employee performance. HR is also tasked with making strategic decisions with respect to how to pay those employees. This lesson will address a variety of influences that determine how pay is structured in organizations.

Lesson Objectives

Upon successful completion of this lesson, you should be able to

- identify the manner in which federal and state law affects wages;

- describe how organizations create pay structures;

- explain the various roles pay structures play in dealing with organizational stakeholders, especially employees; and

- describe and explain how employees judge the fairness of their pay checks.

Lesson Readings & Activities

By the end of this lesson, make sure you have completed the readings and activities found in the Lesson 9 Course Schedule.

The Paycheck

One of the most common understandings of the human condition is that at some point we transition from adolescence to adulthood, at which time we are expected to “earn a living”. Consider the two components of that phrase. “Earn” suggests that we will have to engage in activities that would justify payments for some type of work. Some people live quite well an entire lifetime from bequests and other transfers of wealth; however, most of us “earn” a living by going to job most business days. And the word “living” suggests the need to receive sufficient compensation to support ourselves. We might contrast “earn a living” with “eke out a living”, which suggests an inadequate or barely minimal income.

This lesson will focus on the most commonly debated area of compensation: the paycheck.

The Paycheck: An Employer’s Perspective

The text provides students with an excellent description and analysis of the variety of issues an employer must address in developing comprehensive policies resulting in pay structures. From the employer’s point of view the structures must accomplish a variety of objectives related to the organization’s mission.

- It must be constructed consistent with the employer’s need to attract fully qualified applicants to the types of positions that are required to produce products and services required to achieve the organization’s strategic objectives.

- It must be constructed in a manner that will help retain talented incumbents. In this respect it must be viewed as “fair” by employees in order to prevent voluntary turnover that would otherwise be preventable.

- It must not be so generous as to unnecessarily burden the organization’s balance sheet, which could in the extreme affect its ability to adequately reward or serve other stakeholders, particularly in for-profit enterprises: the shareholders.

The employer therefore will think of the pay structure as a balancing act, always having to reconsider the needs of employees, shareholders and others as it competes in an increasingly competitive environment.

The Paycheck: An Employee’s Perspective

A second perspective that is perhaps less adequately addressed in the text is the paycheck from an employee’s point of view.

We’ve already mentioned the notion that any one of us must at some point earn a living. The paycheck is the most visible illustration of our progress toward that goal. Someone who 20 years later opines about her or his “first job" is likely thinking about the job that marked full-time employment (if actually secured) where supporting oneself was the fundamental objective. The following are some average starting salary figures for college graduates (undergraduate) in the most recent survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers.

|

Discipline |

2014 Average Salary |

2013 Average Salary |

Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Business |

$53,901 |

$54,234 |

-0.6% |

|

Communications |

$43,924 |

$43,145 |

1.8% |

|

Computer Science |

$61,741 |

$59,977 |

2.9% |

|

Education |

$40,863 |

$40,480 |

0.9% |

|

Engineering |

$62,719 |

$62,535 |

0.3% |

|

Health Sciences |

$51,541 |

$49,713 |

3.7% |

|

Humanities & Social Sciences |

$38,365 |

$37,058 |

3.5% |

|

Math & Sciences |

$43,414 |

$42,724 |

1.6% |

|

Overall |

$45,473 |

$44,928 |

1.2% |

Source: April 2014 Salary Survey, National Association of Colleges and Employers.

Clearly certain graduates will do better than others, in other words, be in a better position to earn a living.

Of course, for many beginning the journey in a career whether at the high or low end of this range of starting salaries, wages will represent more than simply their ability to earn a living. For many the wages they are paid represent a form of recognition, particularly if offered as part of merit pay or simultaneously with a promotion. In many cases it represents prestige that some believe elevates their reputation among their colleagues and in their communities.

Interestingly, in college courses of this sort we often focus on starting salaries for college graduates. What we know is that not everyone attends college, and there are many jobs that pay far less than the salaries noted above. According to a recent NPR report,

The four most educated countries — Korea, Japan, Canada and Russia — report that more than 50 percent of their young people have a degree beyond high school, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. By contrast, young adults in the U.S. are barely any more educated than older adults: About 40 percent of both groups have an associate, bachelor's or advanced degree.

Source: NPR: Study: 2 In 5 American Earning Degrees After High School

One sector that has grown extensively is long term care services for older adults, the mentally ill and those who are physically and developmentally disabled. The rank-and-file employee is commonly labelled as a direct care worker. This staff member is responsible for the daily care of individuals who are in significant ways limited with respect to their ability to care for themselves. In some cases the individuals with whom the direct care worker interacts may suffer from ailments that result in violent outbursts that could harm the individual, other individuals and/or the employee. Although there is generally no minimum level of education required to be hired – if only because of the constant need for “bodies” to maintain minimum staffing ratios required by federal and state regulation – new staff receive extensive training not only in ordinary job duties (e.g., how to properly bathe, feed and toilet individuals with those particular needs), but also with respect to how to safely interact in cases where the person becomes violent. The possible penalties for mishandling a violent individual are discipline, placement on an abuse/neglect registry (which prevents future employment in the industry) and/or criminal prosecution. The employee does not have the protection of a weapon nor the protections of a police or peace officer in an encounter of this sort.

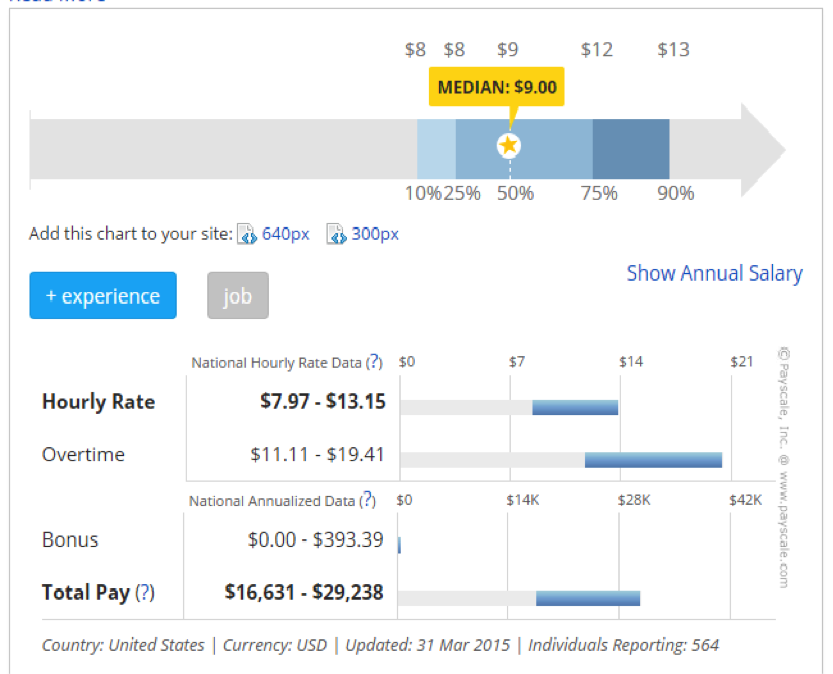

The chart below illustrates a recent survey providing starting wage rates for those hired into these positions.

A quick calculation indicates that in those parts of the country where someone is at the $16,631 per year annualized pay rate, the monthly take-home pay would be $1,279. This, of course, represents what someone would have to live on assuming no additional help and no additional work.

There are, however, opportunities for overtime. Frequently unanticipated illness, call-offs and other employee absences require that a person working a shift remain at work until a replacement can be found. This type of mandatory overtime is common, and for those able to assume that responsibility, the person has the advantage for as many as eight additional hours at overtime rates (assuming the person is not a part-time employee). On the other hand, frequently those who need additional work will assume a second job. The mandatory overtime will sometimes conflict with the beginning of a shift with the second employer resulting in a dilemma: to leave or not to leave? Another dilemma results when the person at work has childcare responsibilities at the end of the initial shift but is ordered to stay pending the arrival (if someone does in fact arrive) of a replacement.

As a consequence lower wage employees whether in this or other sectors of the economy (e.g., entry-level service jobs, retailing) experience high levels of turnover. The turnover might be the consequence of the variations in the business cycle that will cause employers to reduce labor costs, sometimes as the first method to repair deteriorating profit margins. In other cases employees will move from job-to-job seeking a marginally better living, or an environment that puts less stress on their personal lives. In other cases employees trying to balance work and personal lives will be fired as they violate a work rule (i.e., you must remain at work until a replacement arrives) in order to fulfill a similarly important obligation (i.e., take care of a child).

The precarious existence of low wage employees not only in the United States but in many developed economies has generated a very large amount of writing. One of the interesting volumes is Nickel and Dimed by Barbara Ehrenreich. The author spent several months working at low wage jobs in three different employments (in three different states), providing the details of not only the work itself, but the manner in which she ultimately had to live given the size of her paycheck.