EI Versus IQ: A Technical Note

In recent years, we have analyzed data from close to 500 competence models from global companies (including the likes of IBM, Lucent, PepsiCo, British Airways, and Credit Suisse First Boston), as well as from healthcare organizations, academic institutions, government agencies, and even a religious order. To determine which personal capabilities drove outstanding performance within these organizations, we grouped capabilities into three categories: purely technical skills such as accounting or business planning; cognitive abilities such as analytical reasoning; and traits showing emotional intelligence, such as self-awareness and relationship skill.

To create some of the competency models, psychologists typically asked senior managers at the companies to identify the competencies that distinguished the organization's most outstanding leaders, seeking consensus from an "expert panel." Others used a more rigorous method in which analysts asked senior managers to use objective criteria, such as a division's profitability, to distinguish the star performers at senior levels within their organizations from the average ones. Those individuals were then extensively interviewed and tested, and their competencies were methodically compared to identify those that distinguished star performers.

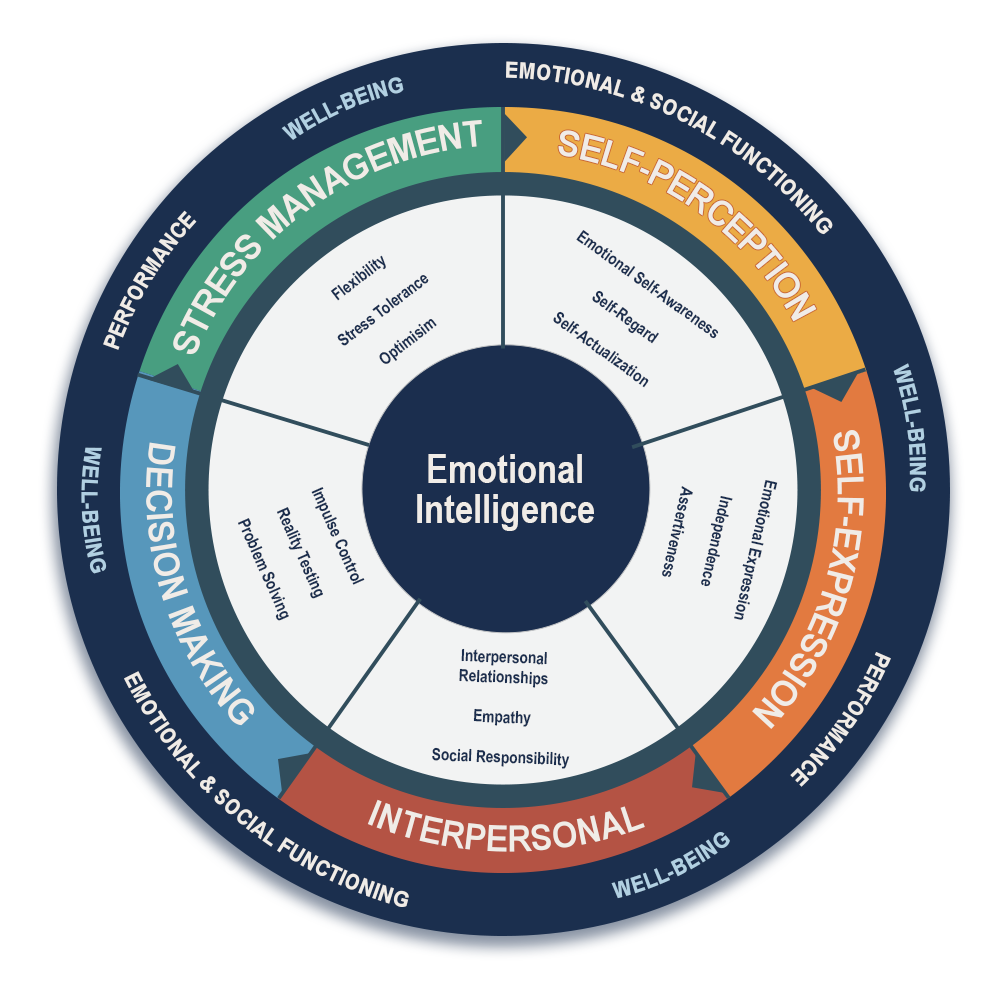

Whichever method was used, this process resulted in lists of ingredients for highly effective leaders. The lists usually ranged in length from a handful to up to fifteen or so competencies, such as initiative, collaboration, and empathy.

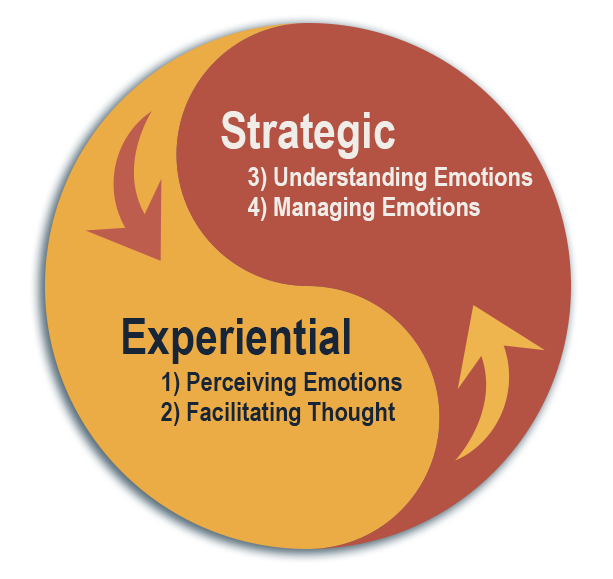

Analyzing all the data from hundreds of competence models yielded dramatic results. To be sure, intellect was to some extent a driver of outstanding performance; cognitive skills such as big-picture thinking and long-term vision were particularly important. But calculating the ratio of technical skills and purely cognitive abilities (some of which are surrogates for aspects of intelligence quotient, or IQ) to emotional intelligence in the ingredients that distinguished outstanding leaders revealed that EI-based competencies played an increasingly important role at higher levels of organizations, where differences in technical skills are of negligible importance.

In other words, the higher the rank of those considered star performers, the more EI competencies emerged as the reason for their effectiveness. When the comparison matched star performers against average ones in senior leadership positions, about 85 percent of the difference in their profiles was attributable to emotional intelligence factors rather than to purely cognitive abilities like technical expertise.

One reason has to do with the intellectual hurdles that senior executives jump in obtaining their jobs. It takes at least an IQ of about 110 to 120 to get an advanced degree such as an MBA. There is thus a high selection pressure for IQ in order to enter the executive ranks—and relatively little variation in IQ among those who are in those ranks. On the other hand, there is little or no systematic selection pressure when it comes to emotional intelligence, and so there is a much wider range of variation among executives. That lets superiority in these capabilities count far more than IQ when it comes to star leadership performance.

While the precise ratio of EI to cognitive abilities depends on how each are measured and on the unique demands of a given organization, our rule of thumb holds that EI contributes to 80 to 90 percent of the competencies that distinguish outstanding from average leaders—and sometimes more. To be sure, purely cognitive competencies, such as technical expertise, surface in such studies—but often as threshold abilities, the skills people need simply to do an average job. Although the specifics vary from organization to organization, EI competencies make up the vast majority of the more crucial, distinguishing competencies. Even so, when those specific competencies are weighted for their contribution, the cognitive competencies can sometimes have quite significant input too, depending on the specific competence model involved.

To get an idea of the practical business implications of these competencies, consider an analysis of the partners' contributions to the profits of a large accounting firm. If the partner had significant strengths in the self-management competencies, he or she added 78 percent more incremental profit than did partners without those strengths. Likewise, the added profits for partners with strengths in social skills were 110 percent greater, and those with strengths in the self-management competencies added a whopping 390 percent incremental profit—in this case, $1,465,000 more per year.

By contrast, significant strengths in analytic reasoning abilities added just 50 percent more profit. This, purely cognitive abilities help—but the EI competencies help far more.