Main Content

Lesson 1 : History and Research Methods

Behaviorism and Gestalt

Figure 1.9. Watson, Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

Figure 1.9. Watson, Public Domain, commons.wikimedia.org

The field of psychology was established well before the calendar turned to the 20th century (1900s), so you might expect that the next hundred or so years would bring about great advances in cognitive psychology. Unfortunately, this was not the case, particularly in the United States. The rise of behaviorism in the 1920s led to a relatively long (approximately 40 years) hiatus from the study of mental processes. The early behaviorists, particularly John Watson, attempted to bring the methodology of psychology closer to the realm of the basic sciences, such as chemistry, biology, and physics. Rather than focus on introspection, they focused their efforts on the relationship between the environment and behavior. In fact, they made a point of not attempting to examine or speculate on the inner workings of the mind.

Instead, they focused on developing methods to look specifically at learning. John Watson looked at a specific type of learning called classical conditioning. One of Watson’s students, B.F. Skinner, advanced Watson’s beliefs and developed theories and phenomenon related to operant conditioning.

Figure 1.10. Skinner, Author: Silly rabbit, commons.wikimedia.org

Figure 1.10. Skinner, Author: Silly rabbit, commons.wikimedia.org

While Skinner and Watson greatly advanced our understanding of learning, one of the central tenets in the behaviorist beliefs was that psychology should not attempt to study or reference any mental state or process that is unobservable (unfortunately, this idea basically excludes all of cognitive psychology).

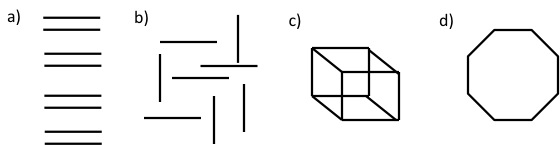

In Europe, around the same time as behaviorism was making a rise in the United States, Gestalt psychology was gaining importance. Gestalt psychology provides interesting insights into our perceptual experiences. The basic tenet of Gestalt psychology is that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” What this is saying in terms of Gestalt psychology is that to understand our perceptual experiences, we need to look at the whole of our perception rather than the individual parts that make up our environment. For example, take a look at Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.11. Example of Perceptual Experiences

All four figures (a–d) are composed of the same lines. Yet our perceptual experience differs drastically with each one due to how we view the entire "picture" and not each individual line. The Gestalt psychologists provided numerous examples such as these to provide support for the idea that our perceptual experience depends on the entirety of our experience and not the individual parts that make up the experience. The Gestalt psychologists proposed many rules for how we group objects but their theories and phenomena never really took off in the United States because of the rise of behaviorism.