Main Content

Lesson 1: Introduction to Leadership

Psychological Safety

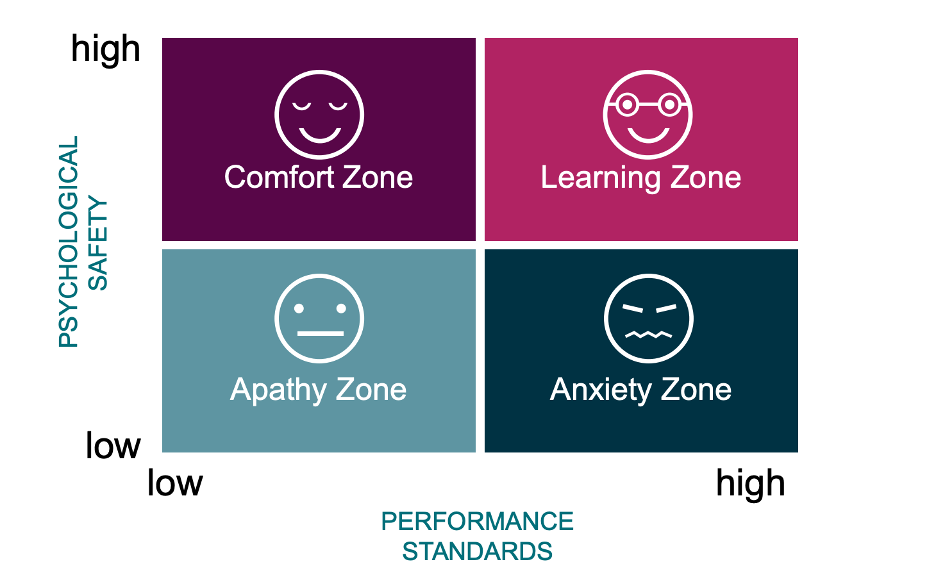

In this course, as with most courses here at Penn State, we are ultimately most interested in creating an experience that maximizes learning. And, research suggests that we do that best when we both (a) challenge students and (b) provide psychological safety as Figure 1.1 indicates (i.e., we are striving for the upper right quadrant).

High performance standards is pretty self-explanatory. In this course, for example, you are challenged to complete a number of different types of assessments to demonstrate learning. Psychological safety, on the other hand is a concept you may not be familiar with. In short, psychological safety is a feeling that one can speak up, change one’s mind, and discuss material without a fear of being reproached or punished by others (Edmondson, 2018).

You might be wondering why we are talking about this in a course on leadership. Well, as it turns out, this concept has been central to research on effectively leading teams. Check out the video below to learn about how research at places, like Google, Pixar, etc. are embracing this idea of psychological safety, and learn more about this from one of the main researchers in this area herself, Dr. Amy Edmondson:

[MUSIC PLAYING]

TREVOR RAGAN: In this package is the first magazine that I've purchased maybe this century. But it's a New York Times magazine from 2016, and in this issue there's an article that has sent me down one of the most exciting rabbit holes I've been down in a long time. I cannot wait to share it with you.

Here we go. "New research reveals surprising truths about why some teams thrive and others falter." This is an overview of a research project that Google did a few years ago called Project Aristotle.

SPEAKER 1: Well, Google has been working for more than four years now to figure out exactly how to best put together successful teams. The results so far are fascinating.

[STATIC]

TREVOR RAGAN: The premise of this study is brilliant. Google's basically like, OK, we have a bunch of teams within our organization. We have a bunch of information about the people on the teams. Let's study this to see if we can figure out what makes the best teams.

Step 1, find out each team's effectiveness. They measure this in four ways. An executive evaluates the team, a team leader evaluates the team, the team members evaluate the team, and then they have the concrete numbers like sales and different outcomes. All this determines how the teams perform, and then they compare that with the information about the people. Where they're from, their age, their skill set, even their personality types. And through years of collecting and analyzing all this data, they found--

[SILENCE]

--nothing.

SPEAKER 2: I hope you're hungry-- for nothing.

TREVOR RAGAN: This quote from the article, it sums it up. "We had lots of data, but there was nothing showing that a mix of specific personality types or skills or backgrounds made any difference. The 'who' part of the equation didn't seem to matter."

After all of these dead ends, they stumbled upon the work of a researcher from Harvard named Amy Edmondson that had the solution to their problem. Amy Edmondson and her team had been studying teamwork for years, and they actually found one specific variable that they thought was the most important. And through lots and lots of work, they found a way to measure this variable.

So Google takes Amy Edmondson's discovery, her variable and her assessment, and plug it into their data. Everything falls into place. It wasn't about the makeup of the team. It's how the team interacts.

Teams that scored higher on this assessment outperform the teams that scored lower on all four of those measures that we mentioned earlier. They make more money, they learn more, they perform better, score higher on the evaluations. So big picture, they discovered that this variable was the key for better group learning and better group performance.

[SWOOPING]

At virtually the same time that Project Aristotle is happening, there's an author, a journalist named Daniel Coyle traveling the world, researching for his new book The Culture Code. He visits a bunch of amazing groups and organizations like Pixar, the San Antonio Spurs, Navy SEALs. And after this long and in-depth journey, what did he find?

DANIEL COYLE: The language we use around culture is kind of hilarious, because it's like, oh, I just get that vibe. It's just got that soft-- that feel, that soft skill that they have. Well, beneath that soft vibe is a really hard science that's totally fascinating. And so that's where I went. And you quickly light upon the work of Amy Edmondson at Harvard.

TREVOR RAGAN: Google and Daniel Coyle weren't aware of one another, and they were going on very different journeys, but they land in the same place on the same topic on the same person, Amy Edmondson.

AMY EDMONDSON: I'm Amy Edmondson, and I'm a professor at Harvard Business School. I have been doing research broadly in the field of leadership and organizational behavior for a long time.

TREVOR RAGAN: Amy is a prolific researcher, and is most well known for her work on psychological safety. Now, she didn't invent the term, but she's on the cutting edge of what it is and how it plays out in different groups. Remember Project Aristotle from Google?

SPEAKER 3: So what we learned is that there are a few common themes that really separate the most effective teams at Google from the rest. But by far, the most important thing is a sense of psychological safety on the team.

AMY EDMONDSON: Basically, my interest, like yours, was learning. And I thought, if you were going to be able to learn, you've got to learn from mistakes. You've got to be able to speak up. You've got to ask for help. Like, if you're going to be able to learn, you've got to feel psychologically safe.

TREVOR RAGAN: Whenever I talk to a researcher, I try to focus on three big things. What is this? Why does this matter? How do we use it? So let's work through these three categories with Amy's help.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So the core idea with psychological safety is it's a feeling that we can be ourselves, that we can ask questions, that we can take risks, we can ask for help, that it is OK to do those things in this group. So in Amy Edmondson's great book, The Fearless Organization, she talks about some of the questions on that survey that measure psychological safety.

If you make a mistake on this team, it is often held against you. Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues. People on this team sometimes reject others for being different. It is safe to take a risk on this team. It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help. My unique skills and talents are valued and utilized. So if you kind of reflect on those questions, you recognize times where we've felt these things and maybe other times we haven't.

It's also worth taking a second and being clear on what psychological safety is not. It's not about lowering standards. It's not about being fake nice. It's not about brushing problems and tough challenges under the rug. In fact, when I talked to Amy, she said it's really the opposite.

AMY EDMONDSON: Are you asking me to relax our standards? And in my view, again, it's almost exactly the opposite there too, because my argument would be in order to achieve high standards, you need psychological safety. You need people to speak up when they're not sure. You need people to take risks that are smart, that they've thought about, oh, this might work. It's like the soil. The soil has to be healthy soil.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

TREVOR RAGAN: I did some digging, and I found all sorts of studies that look at this from all sorts of different angles. But if you go through them, they're all kind of saying the same thing. Psychological safety really matters, especially if we're talking about group learning and group performance.

And big picture, I think it's pretty simple. If we don't feel safe, we're probably not going to do the things that help us grow. We're probably not going to take smart risks. We're probably not going to seek out challenge, probably not going to learn from mistakes, probably not going to ask questions and ask for feedback.

And if the members of the team are avoiding the things that help us grow, it's really hard to learn. And if we're not learning, it's hard to perform well. One of the best summaries of why psychological safety matters is one of Amy's original papers. This is kind of how she first stumbled into psychological safety.

AMY EDMONDSON: I set out to ask a very simple question, which was, do better health care teams-- so teams with better teamwork, better interpersonal relations, better leadership-- do they make fewer medication errors?

TREVOR RAGAN: OK. So here's how they set up this study. They have access to eight teams that are spread across a couple hospitals, a team of physicians and trained nurse investigators. Their job is to track these teams for six months, and they determine the amount of errors each team makes.

And meanwhile, Amy gives each team what they called the team diagnostic survey. So this is before Amy used the label psychological safety, but it was measuring similar things. So the investigators and physicians determined the error rate, and Amy's diagnostic survey gives us a teamwork score. The hypothesis going in, like Amy said, was simple. Well, probably the better teams are going to make fewer errors.

But at the end of the study when they ran the numbers, something really weird happened. The better teams, the teams that scored better on the diagnostic survey, made more mistakes than the teams that scored the worst on the survey.

MICHAEL CERA: Yeah. Wait, what?

AMY EDMONDSON: And of course, after the initial shock, I thought, you know, something's wrong here. Like, this just-- this can't be right, knowing what I knew about the care process. So I stopped to think about it for a while, and maybe they aren't making more mistakes. Maybe they're more able and willing to talk about them.

[SWOOP]

TREVOR RAGAN: So this wasn't actually about which group was making the most mistakes. No. It was which group was reporting the most mistakes. The teams-- the better teams report more mistakes.

Now, this is true in hospitals, but this is true for all of us, no matter who we are, what we do. Owning mistakes, reporting mistakes, and reflecting on those mistakes, that is learning in a nutshell. That's how we grow from a setback. That's how we grow from an error. And if we're not owning them, if we're not reporting them, we can't reflect on them, we can't fix them.

The better teams report more mistakes. They're more likely to grow from them. And in this case, that means they're saving lives. And the groups that don't feel safe to own them and report them, not only are they missing out on opportunities to grow, there's literally lives at stake.

So we've hammered home what psychological safety is, and we've spent a ton of time on why it matters. But now we need to get into the most important piece.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

How do we actually build it? The studies, the book, they outline a lot of effective strategies that can improve psychological safety. For the rest of our conversation, I actually only want to talk about one. Modeling vulnerability builds psychological safety. And once you understand that simple equation, you see it everywhere.

We've all been in a meeting or at a presentation. They ask for questions. What happens? Usually crickets. But after some awkward silence, one person raises their hand. What happens next? 20 people raise their hand. One courageous act, one person being vulnerable and asking a question creates a safer climate for others to do the same.

AMY EDMONDSON: Each and every one of us can show up at work and make a difference in terms of creating the healthy learning climate in our team or with our colleagues. Just how I-- just how I show up actually matters. It can have a profound impact on just the few people around me.

TREVOR RAGAN: One of my favorite leaders and learners is Karch Kiraly. You might have heard of him. He's the head coach of the US Olympic women's volleyball team. And he's famous for setting up lots of one-on-one meetings with his players. And at the end of every meeting, he looks them in the eye and asks the same question. How can I be better for you?

Now, if you think about it, that question will probably lead to some powerful conversations, and he'll get some good feedback. But now with our knowledge of psychological safety, I hope you see what he's really doing is modeling.

Imagine you play for him, and every time he meets with you, he's asking you for feedback. Hey, how can I be better for you? It is now safer for you to ask him for feedback someday.

We can use a similar strategy. What are the actions that you want to see more of from the people around you? Find ways of putting those actions on display.

A school I work with did a project they called the Anti-Talent Show. Every student, every teacher picks something that they can't do. They get to practice it for two weeks. They hold the Anti-Talent Show. Some people learn to ride skateboards, juggle, recite poetry, paint.

I got to visit the school after they completed the project. And I asked some of the students, what was your favorite part of the Anti-Talent Show. One student raised her hand, and she goes, the best part of the Anti-Talent Show for me is that I got to see my teacher struggle, and that helped me understand it's OK for me to struggle too.

Wow. So modeling in this scenario was not just the teacher showing the student how to ride a skateboard. No. It was something bigger and more vulnerable. The teacher was modeling the learning process, the willingness to try something new, to make a mistake, to struggle. That created an environment where it was safer for the students to do the same.

And think about how powerful that can be. When we choose to take action, we improve the psychological safety within the group, but that also encourages more action. That can compound, and that's how you build a better learning environment from the ground up.

If you're interested in learning more about psychological safety, we'll put some links below. If you're in an environment that feels psychologically safe but you're still not taking action, I think my TEDx Talk on fear would be a great resource for you. We'll link that up as well. The last thing I want to say is a huge thank you to Amy Edmondson. You rule.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

If you liked this video, check out the article reflecting it - Better Leadership & Learning: A Guide to Psychological Safety.

So, what does this mean for us in this course?

- Expect moments of discomfort

Remember, we want to be stretching our knowledge and learning in this course. That means we will not always be comfortable and we may interact with some content, comments, students, and even an instructor and possibly a teaching assistant we disagree with at times. Remember that it’s okay to feel some discomfort or frustration while you learn new information and perspectives. IF the level of discomfort creates a barrier to learning, please reach out to your instructor (see point 4 below).

- Practice being a little vulnerable

It’s not always easy to speak our mind. We often worry about being seen as ignorant or bad. But, holding back in those moments often causes us to miss opportunities to learn and grow. So, practice being vulnerable. For example, ask a question even if you worry someone may find it silly.

- Give fellow students and your instructor the ‘benefit of the doubt’

Remember, that your fellow student and your instructor may be practicing vulnerability. If you read something that someone wrote or listened to something another student, instructor, or teaching assistant said and it does not sit well with you, give it a minute. Remind yourself that the other person likely did not have any ill-intent.

- Speak up if your discomfort persists, so everyone can have a chance to learn and grow

Often, we share information and ideas without realizing how those thoughts affect others. Hearing another person’s reaction allows us to visit our thoughts again from a new perspective. It’s allows learning to happen.

More importantly, there may be times when someone makes a mistake. Perhaps they chose their words quickly or poorly.

If you have any concerns about the course content, teaching assistant or instructor’s announcements or feedback, please contact the instructor. If the concern you have is with another student, and you do not feel comfortable discussing the concern with that student, please contact your instructor to discuss how you might proceed.

- Do NOT share quotes from class, Canvas, videos outside of class – because context matters!

As we explore this topic of leadership and examine how the research we are learning applies to different leaders, it’s possible you may say or read something that surprises you. For example, a team in the course may take on the challenge of examining a controversial leader. It would not be fair to those team members, your instructor, this course, nor this institution to take a quote or clip from their work and share it outside this course where it could raise concerns of others that are not experiencing the full context of this learning experience.

In addition, you will be asked from week to week to share examples applying the course material to your life and work experience. You will never be asked in this course to share highly personal information or disclose company secrets; all discussions will focus on leadership issues. That said, all students should feel free to share their real life work experiences here without concern that their words could be used against them in the current or future work place. It is also acceptable to change the names of people in any scenarios you choose to share from your personal experience for the sake of confidentiality.

For all the reasons mentioned above, it is important that we do NOT share course material in ANY way outside this course. This is true for everyone. Your instructor will also not share your work or writing outside this course (i.e., your work in the course is not being collected for research nor publication; all assessments are focused on helping you learn and/or assessing what you have learned. In the event that your work is exceptional, and the instructor would like to consider using it as an example for other students, you will be formally asked if that is okay and whether or not you would like to be identified with that work.

In your written assignment this week, you will be asked to indicate your agreement with the points above. If you have any questions about this at all, please contact your instructor as soon as possible.