Main Content

Lesson 2: The Development of Cinematic Language

Strikes and Prison

It's interesting that the law or police officers end almost every sequence and has every possibility of happiness for the Tramp. Here, as elsewhere, the law is the protector of private property and the interest of big business, not the protectors of justice. This was not only something that you see in Chaplin's films in general, but it was also a very popular sentiment in the 1930s, very widely held. Note how the law here is represented in relation to the question of labor and the right to organize.

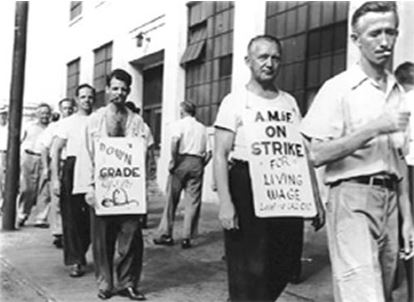

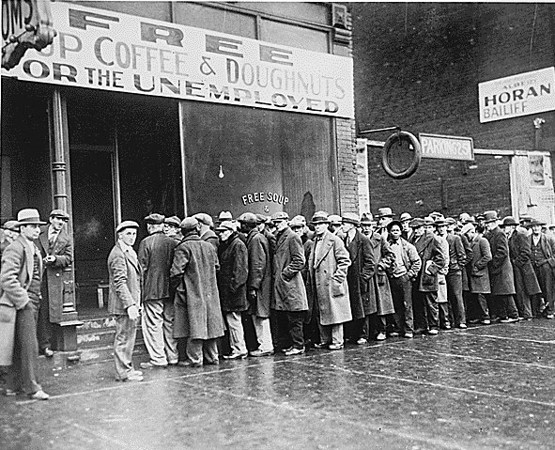

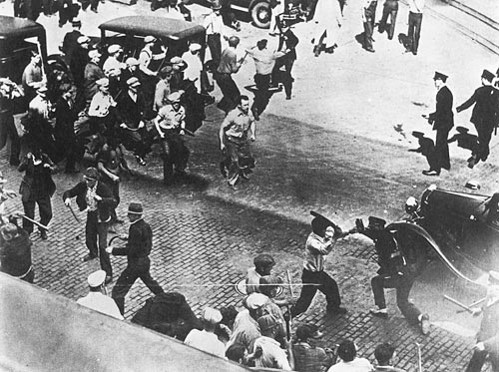

Figures 2.17 through 2.20 show photos of the 1933 mine strike, bread lines, a communist protestor, and the general strike in San Francisco in 1934.

|

|

|

Figure 2.19: 1934 San Francisco general strike. |

|

These were things that were everywhere. Chaplin is using comedy to comment on things that were pressing on society, he believed. With the Tramp ending up every sequence, he ends back in a place that seems to be better than living out in the real world with all its excitement, which is prison.

The irony is that Chaplin doesn't want to leave prison. The warden is telling him, after your good work, you can go. Chaplin is saying I'm so happy here, I don't want to leave. I have everything I need here. The Tramp is somebody who is mostly concerned with having his basic human needs met, which are food and rest and warmth and shelter, and now he has to go back out and struggle in the outside world.