Measuring Crime

There are several methods that are used to measure crime in the U.S. The first is often referred to as the official measure of crime. The 16,000 plus local police departments across the U.S. report their crime to the F.B.I. Those crime statistics are then aggregated and reported out in the F.B.I.’s Uniform Crime Reports (UCR). Part I offenses of the UCR include murder, aggravated assault, rape, robbery, arson, burglary, larceny/theft, and motor vehicle theft. Part II offenses include all other types of crime, such as prostitution, drug trafficking, etc. Although the UCR data are a good source of information about how much crime and what type of crime is occurring across the U.S. in any given year, they are not without their problems. The UCR data consists of those crimes known to the police and for which an arrest was made. What about the so-called “dark figure of crime,” or, those crimes that go unreported or those crimes for which no arrest is ever made? Too, the F.B.I.’s Hierarchy Rule calls for only the more serious of multiple charges to be reported in annual crime statistics. If, for example, an offender assaults a police officer during the arrest associated with drug dealing, only the assault will be reported as it is the most serious offense. Finally, crime is not always defined in the same way across states. In Pennsylvania, for example, burglary may be legislatively defined one way, while in Louisiana, it might be defined differently. It becomes, then, the old “apples vs. oranges” dilemma.

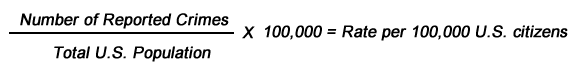

Still, the UCR data are the main source of crime data in the U.S. today, in spite of the problems associated with it. A highly reported statistic is based on those data. The crime rate in the U.S. and across its various communities is calculated using UCR data and as:

It is through the use of this equation that we can look at how crime (at least officially) has changed over time. Today, for example, the official look at crime tells us that there are about 1.4 million violent crimes occurring each year or at a rate (using the above equation) of around 466 per 100,000 Americans.

National Crime Victimization Survey

A second way that crime is measured in the U.S. is the annual National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), a survey of over 77,000 households in which family members (at least 12 years of age) are asked about their personal experiences with crime. Unlike the UCR data, the NCVS collects information about the characteristics of the crime event itself. Victims are asked to describe to the interviewer what happened to them and then those incidences are coded (burglary, robbery, aggravated assault, etc.) and placed into the larger data file. Because of the highly sophisticated nature of the methodology and statistical tests applied to the NCVS, the data are considered to be valid and reliable measures. Some argue that the NCVS is a more accurate picture of crime in the U.S. as crimes that are not reported to the police are discovered and included in the numbers. This does not mean, however, that the NCVS data are free of problems. For one thing, victims may be reluctant to report the incident to the reviewer, or they may be reporting on something that happened to them outside the time frame that they are asked to think about (e.g. reporting on something that occurred within the last 14 months when they are being asked to report on victimizations that occurred within the last 12 months).

Self-report Studies

Sometimes people are simply asked to self-report their criminal or delinquent behaviors. Self-report surveys are used, for example, with adolescents and adults to measure the extent and nature of drug, alcohol, and tobacco use. Well known theorist Travis Hirschi (1969) used a self-report study to measure delinquency among high school students in the Oakland, CA area, finding a relationship between a lack of social bonding and delinquency. Just like the NCVS, self-report surveys can provide information about crimes that might have gone unreported to the police. On the other hand, one problem that must be considered is that of whether we can depend on people to tell us the truth about their crime, delinquency, drug use, or other deviant behaviors.

In sum, these three ways that we have to measure crime in the U.S. are not without their problems. What is interesting, however, is that quite often comparisons are made between the data associated with one type of measure and that of another and similarities are found. This leads to an overall conclusion that although they are not error free, they do appear to give us somewhat reliable estimates of the extent and nature of crime.