Main Content

Lesson 1: Overview of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism Spectrum Disorders

If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.

Individuals with autism are a very heterogeneous group. You may personally know someone with autism—you may work, go to school, have a friend, or have an acquaintance with autism. As you no doubt know, each person's characteristics make them who they are. Although we’ll be discussing common characteristics, teaching strategies, and other educational issues related to autism, generalizations about characteristics can be inaccurate or can mask uniqueness. Remember that no size fits all; throughout your life, you’ll interact with unique and special individuals with autism.

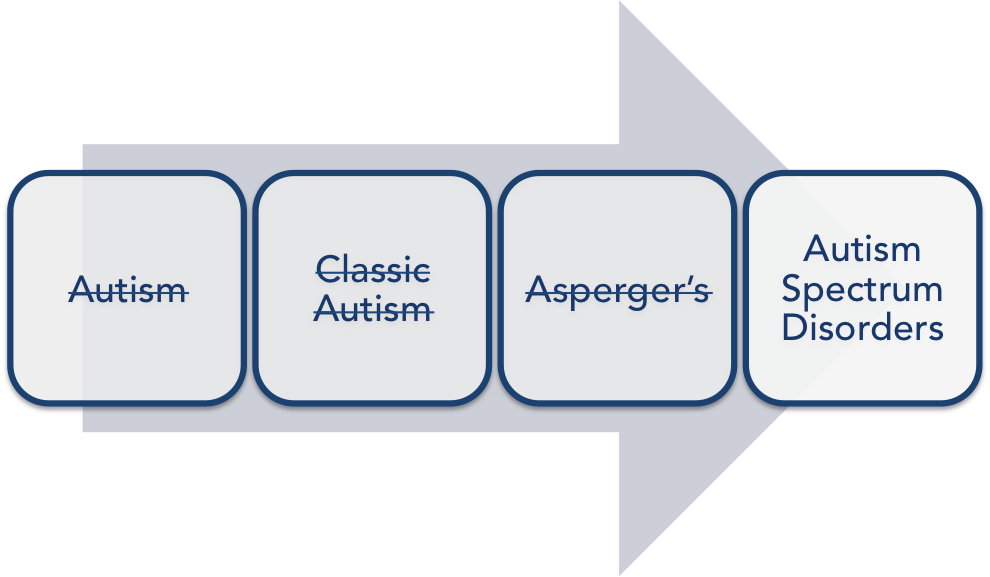

Before we begin, let’s talk about language and terminology. You may hear a lot of terms associated with autism. At present, the term autism spectrum disorders (or ASD) is used to replace such diagnoses as autism, classic autism, or Asperger’s. The new term ASD emphasizes that autism is a “spectrum” disorder, with a lot of variability in strengths and needs among those with the disorder.

This lesson's readings will provide you with an overview of ASD. First you will read about recent changes made to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or the DSM. The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and is the primary manual used by clinicians to provide a formal diagnosis. The DSM outlines specific criteria needed to receive a diagnosis, provides labels or names for the diagnosis, and lists the numerical codes that are sometimes used by insurance companies to bill for services. Essentially, the DSM provides the standard guidelines for clinicians to use for a formal diagnosis. After you read about the DSM, the lesson will cover potential causes of ASD, characteristics of the population with ASD, and instruments used to diagnose ASD. Finally, you'll look at the general parts of an individualized education plan (IEP) and how one might write a goal for a person with ASD. Let’s start with the DSM.

The DSM-V

The latest edition, the DSM-V, was published in 2013; it covers many different disability and diagnostic categories (such as intellectual disabilities, attention-deficit disorder, and other medical conditions). Most of the diagnostic categories have remained unchanged. However, in the recent edition of the DSM (V), there have been major changes to how ASD is diagnosed. Why was the DSM changed? Well, clinicians wanted to make the ASD diagnosis more specific to provide greater sensitivity, so that true cases would be identified. They also wanted the criteria to be more reliable (so that clinicians would agree on who had ASD), to be valid (accurate), and to really reflect that ASD is a set of behaviors. As seen in the DSM-V, ASD is characterized not by separate symptoms, but by a particular set of behaviors that manifest themselves together.

The changes in the DSM are relatively new; in fact, they're the first substantial changes to the manual in 13 years. As you can imagine, the systematic use of the DSM-V will take time. You may continue to hear terms that are no longer in the DSM-V (like Asperger’s). However, for accuracy, we will be using only the new terms and criteria. Below, you will find two charts; one outlines the changes made to the ASD diagnosis from the DSM-IV to the DSM-V. If you’ve had contact with individuals having ASD, you’ve likely seen a great deal of variability in how well each person is able to function. As outlined in the diagnostic criteria, there are two central deficit areas: social communication deficits, and restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. Recently added to the latest version of the DSM is a rating (from one to three) of the severity of the deficit areas. For example, an individual may be diagnosed as Level 3 in the area of social communication, but have less-severe symptoms of repetitive behaviors, which need only a moderate level of support (Level 2). Currently, there are no specific guidelines on how to assign a severity level.

|

|

DSM-IV |

DSM-V |

|---|---|---|

|

Definition |

|

|

|

ASD subtypes |

|

|

|

Clinical features |

ASD was characterized by three core symptoms:

|

In the DSM-5, there are now just two symptom categories:

|

|

Onset |

Onset before 36 months of age |

Now there is more of an open definition: “Symptoms must be present in early childhood, but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities.” |

Adapted from Diagnostic Criteria for Autism Under the DSM-5, by G. Vivanti, O. Tennison, and D. Pagetti Vivanti, 2016. In Autism Europe: About Autism.

The second chart shows the recently added severity scale, which describes the impact of ASD on everyday function.

|

Severity level |

Social communication |

Restricted, repetitive behaviors |

|---|---|---|

|

Level 3 "Requiring very substantial support” |

Severe deficits in verbal and nonverbal social-communication skills cause severe impairments in functioning, very limited initiation of social interactions, and minimal response to social overtures from others. For example, a person with few words of intelligible speech who rarely initiates interaction and, when he or she does, makes unusual approaches to meet needs only and responds to only very direct social approaches. |

Inflexibility of behavior, extreme difficulty coping with change, or other restricted/repetitive behaviors markedly interfere with functioning in all spheres. Great distress/difficulty changing focus or action. |

|

Level 2 "Requiring substantial support” |

Marked deficits in verbal and nonverbal social-communication skills, social impairments apparent even with supports in place, limited initiation of social interactions, and reduced or abnormal responses to social overtures from others. For example, a person who speaks simple sentences, whose interaction is limited to narrow special interests, and who has markedly odd nonverbal communication. |

Inflexibility of behavior, difficulty coping with change, or other restricted/repetitive behaviors appear frequently enough to be obvious to the casual observer and interfere with functioning in a variety of contexts. Distress and/or difficulty changing focus or action. |

|

Level 1 "Requiring support” |

Without supports in place, deficits in social communication cause noticeable impairments. Difficulty initiating social interactions and clear examples of atypical or unsuccessful response to social overtures of others. May appear to have decreased interest in social interactions. For example, a person who is able to speak in full sentences and engages in communication but whose to-and-fro conversation with others fails, and whose attempts to make friends are odd and typically unsuccessful. |

Inflexibility of behavior causes significant interference with functioning in one or more contexts. Difficulty switching between activities. Problems of organization and planning hamper independence. |

Adapted from DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria, by Autism Speaks, Inc., 2016. In Autism Speaks: What Is Autism?