The Book as a Physical Object - Part I

With picturebooks, sometimes the physical structure of the book itself can be a carrier of meaning. What follows are some basic terms for parts of a picturebook.

A. Book Size

Books can be physically small. Beatrix Potter's books are familiar to many readers because of their small size -- just right, she thought, for small hands to hold. Physically small books today tend to be board books -- books printed on thick cardboard and intended for babies. Because the books are so small (The Tale of Peter Rabbit measures 4" X 5.25"), the illustrator doesn't have much of an area to use. Thus, illustrations tend to be simple in composition.

![]() Go to the Web Resources link for The Tale of Peter Rabbit to see images

and get more

information.

Go to the Web Resources link for The Tale of Peter Rabbit to see images

and get more

information.

Likewise, books can be physically large.

Foolish Rabbit' s Big Mistake is a an example of physically large book (11.25" X 10.25"). The larger working space enabled Ed Young to create very large illustrations, providing a dramatic effect. You can think of this as the difference between watching a movie in a big screen theatre and watching a recording on a television. The larger screen makes a more profound impact on our senses.

We will also learn later from Molly Bang's Picture This, that the larger the object, the more narrative weight that object holds.

B. Book Shape

The shape of the book can suggest something about the nature of the story. As we saw earlier, Rosie's Walk, when opened is a short, wide book. It is a story of a journey, which is a primarily horizontal activity. It has a horizontal shape that is accentuated when the book is opened.

Look at the following pictures from The Ox-Cart Man, by Donald Hall and illustrated by Barbara Cooney, to see how the shape of that book resonates with the walking journey the farmer takes in the story.

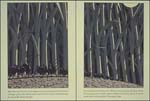

Chris Van Allsburg's Two Bad Ants is also a journey book, but one that is told from an ant' s perspective. Van Allsburg guesses that the world must seem very vertical to an ant, so the book is taller than it is wide, which creates a vertical effect. Van Allsburg divides his illustrations into vertical panels, so that even when the book is opened, the accent is maintained on the vertical.

C. Cover and Dust Jacket

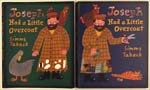

The cover is just that, the cover of the book. Usually, in American books, the illustration on the dust jacket is a copy of the illustration that has been laminated onto the front of the book. And often that illustration is one that has been lifted from the pages of the story. Sometimes, illustrators make different illustrations for the cover and the dust jacket. Sims Taback's Joseph Had a Little Overcoat is an example of a book where the cover illustration is different from the dust jacket. In the following image the dust jacket is on the left and the cover is on the right. The white spots are actual holes that show through to the overcoat underneath. This is suggestive of the story as pieces of the overcoat fall apart throughout.

The front inside flap of the dust jacket traditionally carries information about the book (called a blurb) that will entice someone to purchase or read the book. The back inside flap usually carries biographical information about the author/illustrator of the book. Lane Smith is an illustrator who often plays with the inside flaps, in sometimes unconventional ways. In the tenth anniversary edition of The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, an additional story was printed on the inside of the jacket itself. For an unconventional artist such as Lane Smith, any surface on the book is a potential space to illustrate, even spaces you may have to search for.

![]() Be sure to look

at your copy of The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales to

see this concept demonstrated.

Be sure to look

at your copy of The Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales to

see this concept demonstrated.

D. Binding

The binding is what holds the pages of the book together. Most books have either a stitched binding or a glued binding. Or in the case of some mass-market paperback picture books, the binding may be stapled. Stitched bindings tend to be more durable, but are less likely to lie flat. Illustrators working with double-page spreads will take this into consideration. Because some of the illustration would be lost in the binding (the middle of an open book is called "a gutter"), the illustrator who is planning a double-page spread will try to be aware of where the binding break will occur.